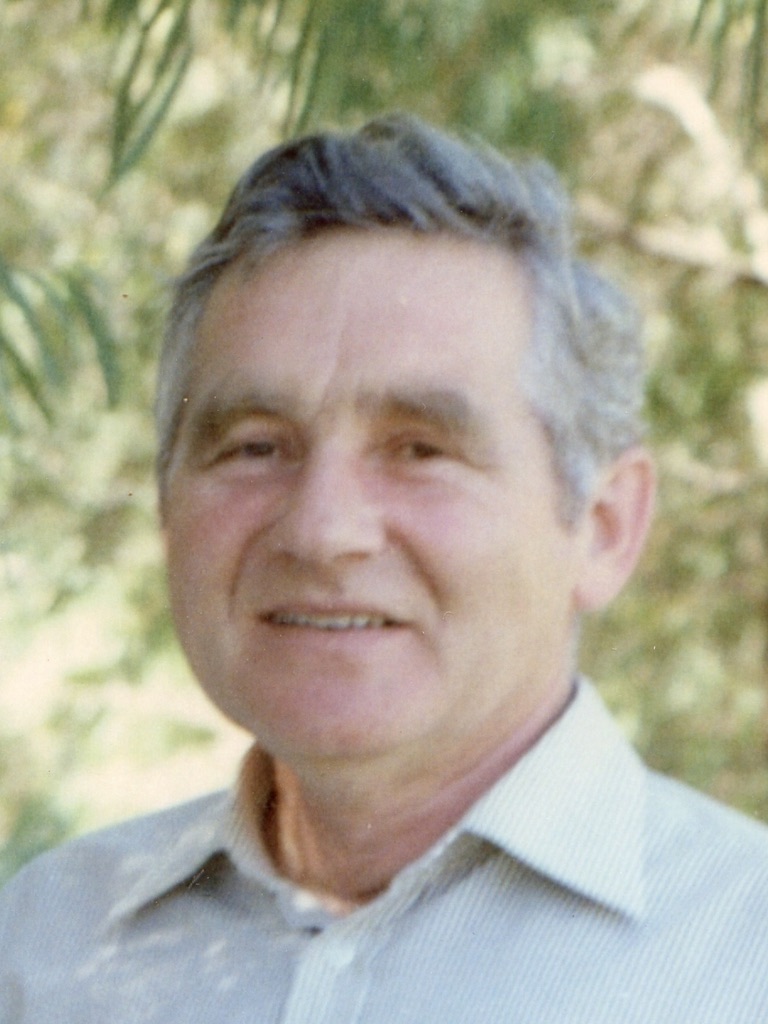

A photo of Julius Kovesi from the 1950s

ANTHONY KENNY

Julius and I first met in Oxford in 1957. I was then a Catholic priest, having been ordained in Rome as a student of the English College in 1955. I had now been seconded to Oxford for an academic year to complete a dissertation on linguistic analysis and the language of religion to be submitted as a doctoral thesis to the Pontifical Gregorian University. Julius was a graduate student in the second year of his B.Phil course in philosophy, working under the supervision of Richard Hare. Julius was a member of Balliol, the college where Hare was a tutor; I was a member of the much less prestigious St Benet’s, a small Catholic private hall. We met through the Roman Catholic Chaplaincy, under the auspices of Mgr Valentine Elwes, and still haunted by the ghostly presence of Ronald Knox. We were much of an age: Julius was a few months older than me, and we were both several years above the average age of philosophy graduate students.

It was an exciting time to be a student of philosophy at Oxford. The late fifties were the heyday of linguistic philosophy: philosophers were confident that they had discovered new philosophical methods that superannuated much of the metaphysics of the past. Ludwig Wittgenstein was not long dead: the gradual posthumous publication of his works allowed his genius to be appreciated not only by the small circle of his Cambridge pupils but also by the philosophical world at large. Linguistic philosophy was in its ‘ordinary language’ phase, and after Wittgenstein’s death Oxford came to be regarded as the centre of this movement. It had the largest philosophy department in the world. John Austin and Gilbert Ryle, Professors of Moral Philosophy and of Metaphysics respectively, were both inspiring figures. Austin, a sharp and witty lecturer, and Ryle, a brilliant writer, were both devoted teachers and worked hard to foster young talent. From all over the English-speaking world philosophers gathered to sit at their feet, and at the feet of Oxford figures then holding junior posts. Prominent among those was Richard Hare, still only a tutorial fellow of Balliol, who was to have a significant influence on the careers of both Julius and myself.

Naturally enough, we were both greatly influenced by the Catholic philosophers at Oxford. Pre-eminent among these was Elizabeth Anscombe, even though she held only the humble post of lecturer at Somerville. Her seminars on Wittgenstein were for me the most important educational experiences of my life; I cannot now recall whether Julius was a regular attendant. Elizabeth’s husband, Peter Geach, then teaching at Birmingham, appeared from time to time at Oxford philosophical occasions, carrying a pocket edition of Aquinas’ Summa Theologiae which he would produce to quote passages to puncture trendy theological persiflage produced by unwary clerics at Catholic gatherings in Oxford.

Among the Catholic philosophers, dons and students, whom I met through the chaplaincy, Julius quickly identified himself as one of the most original and attractive. His immediate response to any problem—whether philosophical or practical—was to enunciate, with a perfectly straight face, some totally incredible and impossible solution. Only when, after a pause, the rest of us would realise that it was not seriously meant, would his face pucker into an enormously engaging smile. Then a less exciting, but more credible, solution would be forthcoming.

Julius and I, I am sure, must have had many serious and weighty discussions about issues of ethics and philosophy of religion. But what remains most vivid in my memories of him is our collaboration in producing a samisdat periodical called WHY? This was a collection of philosophical spoofs and parodies, produced in cyclostyle by Julius on the Balliol office machine. Julius introduced it in his editorial to the first issue as follows. ‘The value of Philosophy is to protect us from other philosophers. But who will protect us from ourselves if we take ourselves too seriously? So here is WHY which intends to provide this very important second-order protection.’

Both Julius and I had previous experience of editing scurrilous periodicals. Julius, as a schoolboy in Hungary had produced between 1943-44 a student newspaper called FORR A BOR (‘The Wine is Fermenting’). At the English College I had edited several issues of Chi Lo Sa? (‘Who knows’) a subversive, though licensed, triennial expression of student contents and discontents. Our first issue of WHY? appeared in February 1958. Julius wrote a large part of the copy himself, with his satires focussed on his interest in ethics. He contributed a piece on The Bad, which lamented that philosophers had concentrated on distinguishing between The Right and the Good rather than on the Wrong and the Bad. As a result of this philosophers had failed to discover how to achieve the greatest misery of the greatest number and to arrive at the Kingdom of Dead Ends. He also wrote a book review of ‘The language of Courtship’ by Mr Alvis—a skit on R. M. Hare’s The Language of Morals.

My principal contribution was a programme for the philosopher’s day (beginning with rising from the ideal bed and checking to see that the sun had risen, including such items as lighting the fire in order to consign to it all volumes of divinity or school metaphysics, and racing a tortoise up the High, and ending with a relapse into dogmatic slumber).

Julius and I, however, were not the only contributors. A Balliol undergraduate contributed a set of agreeable clerihews about pre-Socratic philosophers. (‘Thales bet / that all things were wet / in fact the wetter / the better’; ‘Anaximander / though renowned for his candour / yet eschewed / being rude’). A philosophical Snakes and Ladders was contributed by Janet Green-Armytage, then or later Julius’s fiancee. Julius set a ‘WHY? problem’: ‘Is there any reason for saying that in Australia the winter is in the summer?’

The first issue of WHY? was taken by some to be a manifesto attacking Oxford philosophy. This was rejected in the editorial to the second issue. ‘As well conclude, from the verses which we printed about Thales and Anaximander, that we were launching a campaign against the Pre-Socratics. There is only one sort of philosophy which we intend to attack: that is, any philosophy, anywhere, which cannot afford to laugh at itself.’

The second issue contained, in addition to the answers submitted to Julius’s WHY? problem, spoof lecture lists and examination papers, and a set of variations on the theme of Old King Cole by Hume, Russell, Neurath, Wisdom, Carnap and Ryle. It was my turn to edit the issue, and this time Julius did not submit any signed pieces.

The two 1958 issues of WHY? attracted a certain amount of attention, not all of it friendly. One day Professor J. L. Austin said to me after his class: ‘I see you and Kovesi have taken to bringing out a comic. I am sorry to see him involved in this—he has real philosophical talent and might be spending his time more profitably.’

For the third issue, however, we had a contribution from a don, Patrick Nowell-Smith of Trinity. This was entitled ‘Drinking and Dreaming’ and ended with some Wittgensteinian aphorisms. (‘2.032 Roughly speaking, gin and water is colourless. / 5.44 Not what the stuff is, is the mystery, but how they manage to sell it. / 6.521 The solution to the problem of life is seen in the bottom of the tankard / 7 Wherefore one cannot pay, thereof must one not drink.’)

This appeared side by side with an article by Julius on the Philosophy of Cookery which purported to be a review of one of Nowell-Smith’s own books. The issue concluded with a menu devised for the WHY? association dinner by Janet (by now Janet Kovesi), beginning with Consomme Tortue a la mode d’Achille and Leviathan a la nature.

This issue, of February 1959 was the last to appear. It had been brought out in Edinburgh, where Julius was now based as a lecturer in philosophy. Production of it in Balliol had led to some embarrassment when one day Richard Hare entered the college office while Julius was printing off a satire on his work.

Hare was a devoted teacher, with a missionary desire to convince pupils of the correctness of his views on moral philosophy. He made a deep impression on many of them, but not quite as he wished. Several, notably Bernard Williams, continued until quite late in life to produce criticisms and refutations of the ethical teachings they had heard in his tutorials. Julius’s own book, Moral Notions of 1967, belongs to a similar tradition. Later, as a Fellow of Balliol, I became a close colleague of Hare. I found him a most intelligent and imaginative partner in philosophical conversations—provided we avoided the topic of moral philosophy.

In 1958, while still a Catholic priest, I married Julius and Janet to each other at a church in Bath. When, some years later I returned to Oxford after having been laicised, Julius asked me whether they would have to get married again. No, I said, the marriage of course remained valid, no matter what happened to the cleric who presided. ‘What a pity’, said Julius, ‘I like getting married so much that I would like to do it again’.