Alan Tapper and Janet Kovesi Watt

Janet Kovesi in 1988

Julius Kovesi, who died in 1989, published only one book, Moral Notions, which appeared in 1967. This present book brings together most of his published and unpublished papers. It is a substantial collection, covering a variety of topics, and it will help to assuage the feeling many of his friends had that he did not produce the books that we felt he was uniquely equipped to write. That feeling arose in part from the impact that Moral Notions had on those who read it carefully, but even more from the impact that Julius Kovesi had on those around him. He seemed to have so much to say that was quite unlike anything being said by others. We expected that he would eventually say it in books–a successor to Moral Notions, a book on modern theology, an analysis of Marxism, something on Plato–but at his untimely death the books were unwritten. What he did write is here.

Philosophers who are ‘known’ are, of course, known by their surnames: Russell, Austin, Quine etc. Kovesi was not in that sense a ‘known’ philosopher. To all who knew him, from first-year students to eminent professors, he was known simply as Julius. That is how he wanted to be known. For some years his office wall carried a child’s story book picture of a gorilla emerging from the jungle and announcing ‘My name is Julius’. The convention is that, in a book such as this, he should be known as Kovesi, but to those who knew him this will feel wrong; those who did not know him might want to know that about him.

Hume exhorted philosophers to ‘Be a philosopher; but amidst all your philosophy, be still a man’. Two hundred years later, when philosophy has become more than ever a professional occupation, and some even make professional philosophy their life, this is good advice, but it perhaps assumes that philosophers are somehow philosophers first, and men or women second. In Kovesi’s case it was clearly the other way around: he was a philosopher because he was someone who had lived the life he had lived. Julius the person preceded Kovesi the thinker; he became the thinker he was in order to remain the person he had always been. Not to think as penetratingly as he could about the world he lived in–a world of conflict, ideology, and moral confusion–would have been a self-betrayal, a deliberate forgetfulness about his everyday experience. All those who knew him felt the force of his honesty, simplicity, humour, integrity and unconventional wisdom. This introduction will attempt to introduce the thinker and the man, and preferably both at once, for his philosophy and his life were all of one piece.

A brief biography is called for here, to give an outline of the experiences that helped to shape his thinking. He was born in Budapest in 1930, and grew up in a country town in Western Hungary, Tata, a lakeside resort favoured by previous occupying powers, including the Romans and the Turks. His brother described their idyllic life in pre-war Hungary as ‘like growing up in the nineteenth century’. The mid-twentieth century brought war, invasion, and occupation first by German troops and then, after prolonged fighting in the countryside near their home, by the Russians.

At the time when communist government was established in Hungary Julius and his brother were students at Budapest University, where Julius attended the philosophy lectures given by Lukacs. As communist rule became increasingly oppressive, and barbed wire began to encircle the country, they decided to escape while it was still possible, only to be caught at the Austrian border. Julius, even then ideologically quick on his feet, told the guards that he and his brother were not rejecting communism, they were only foolish young bourgeois students who wanted to see Paris before the final collapse of capitalism. Whether or not this was a convincing defence they were released, after a beating, but only on condition that they reported on fellow-students who might also be planning to escape. Within days they again headed for the border, and this time succeeded in crossing it.

Eventually they made their way to Innsbruck and studied there before deciding, with their parents who had now joined them, to take the opportunity of migrating to Australia.[1]

Six year after arriving in Western Australia Julius had mastered English, completed a first class honours degree in philosophy, and had been awarded a scholarship for postgraduate study at Balliol College, Oxford. No sooner had he arrived in Oxford however, in late 1956, than the Hungarian revolution broke out, and he was given leave to go to Austria to work as an interpreter for refugees, thereby helping others in the same predicament that he had himself been in a few years before. From them he learned at first hand what it was like to try to resist a communist government that was now backed up with Russian tanks and artillery as well with guards and barbed wire at the border.

Back at Oxford, besides studying for the degree of B. Phil. and writing his thesis (on ‘How good is “The Good”?’) Julius collaborated with Anthony Kenny in producing a journal of philosophical parody called Why? which is still widely remembered.[2] The first editorial (there were three issues) set the tone by declaring: ‘The value of philosophy is to protect us from other philosophers. But who will protect us from ourselves if we take ourselves too seriously?’ Julius was never in danger of that, but he meant the first sentence to be taken seriously, and often had occasion to quote it later on. He knew only too well the power of apparently-impressive arguments to bemuse and oppress, and for the rest of his life devoted his energies to helping others to see through them and resist them. While the jokes and parodies in Why? were overwhelmingly light-hearted and good-humoured, on later occasions, notably in the writing of Trialogue, a journal lampooning ‘modern’ theology, the jokes had a sharper edge.[3] This more aggressive approach was foreshadowed in the second Why? editorial: ‘There is only one sort of philosophy we intend to attack: That is, any philosophy, anywhere, which cannot afford to laugh at itself.’

The philosopher who had the greatest influence on Julius’ thought during his time at Oxford and for some years afterwards was his supervisor, J.L. Austin, whose penetrating, precise and witty analysis of ordinary language was the embodiment of the Oxford linguistic philosophy which flourished in the 1950s. His style of philosophising was affectionately parodied in Why? in a spoof book review of The Philosophy of Cookery, which described

Professor A*st*n’s completely original approach to the problem. Instead of simply considering ‘to cook’, he investigates ‘cook with’, ‘cook for’, ‘cook at’ and ‘cook up’. One must mention his well-known lecture on the distinction between ‘boiling’ and ‘broiling’. We do say we embroil but we do not say we emboil…. He prefers the language of a plain cook who says ‘take two eggs’. ‘But how do you separate two eggs? Do you separate two eggs as you separate two eggs when they are stuck together or as you separate two separate eggs? Do you do the same when you separate two potatoes as when you separate two eggs? You can separate an egg. Now separate a potato. Why cannot you separate a potato? Usually we say that we cut a potato.’

Julius’ gifts, both intellectual and social, blossomed at Oxford. He was particularly delighted by the many Oxford societies, from the seriously intellectual Socratic Club[4], to the rather less serious or even exuberantly frivolous societies based on Balliol. During his final year at Oxford Julius himself founded a society, modelled on the Socratic Club, for the discussion of philosophical and religious topics from a specifically Catholic viewpoint, and attracted a remarkably distinguished group of Catholic philosophers to its meetings. Later in his academic life he was to gather around himself other more informal groups, modelled on the Leonardo Society at Balliol, for the reading and discussion of papers on a wide variety of philosophical, historical and literary topics. It was an aspect of his life that gave him enormous pleasure, and he cherished the friendships that grew out of such gatherings.

After leaving Oxford Julius spent a year at Edinburgh University, and three years at the University of New England in New South Wales, before returning to the University of Western Australia in 1962. He remained on the staff there for the rest of his life, and there he taught until a week before his death. Though he died before the full collapse of communism in Eastern Europe, he did live to see the opening of the Hungarian border, and the symbolic presentation to President Bush of a piece of barbed wire.[5]

Just before his final exams at Oxford, Austin gave Julius a note reading: ‘Be relevant. Read and answer the question.’ It was a note he framed and kept on his desk for the rest of his career. Readers who have glanced at the Table of Contents will have noted the diversity of subject matter, and perhaps have wondered what if anything might hold it together. Locke, Hume, Marx, Moses Hess, G.E. Moore, biblical criticism, myth, fact and value–these look like diverse interests. Not only do they seem somewhat unrelated to each other, they seem even less obviously related to the problems of the mid to late twentieth century. Yet Kovesi’s philosophy was about this world, even when it involved thinking about the past, and the philosophers of the past. And, in his own view at least, his interests had a unity which he was always trying to articulate, and which made his conversation always likely to jump unexpectedly from the present back to Socrates or to The Epic of Gilgamesh or anything else between then and now.

Kovesi’s interest in history was not of the sort which looks simply for parallels or precursors of the present. It was far more original than that. Comparisons were his stock in trade, but the kind of comparisons he sought can best be expressed by the phrases ‘the same, yet different’ or ‘different, but the same’. The capacity to discern differences in sameness and sameness in differences was the skill which he most sought to cultivate and inculcate. It is a theme in Moral Notions and it is a theme running through his writing on ideological issues. Thinking responsibly about important matters, on his view, just is the process of teasing out similarity and dissimilarity. And thinking philosophically just is thinking carefully and formally about how we recognise samenesses and distinguish differences.[6] On his view it is our lack of skill in handling comparisons and examples that makes our moral life so difficult. His own constant, vivid and memorable use of examples is characteristic. He used to say that he collected examples, even if he did not yet know what they would turn out to be examples of.

Moral Notions was notable for the inventiveness and liveliness of the examples and newly-coined concepts (‘misticket’, ‘saving-deceit’) which were discussed. A central theme of the book was that our moral concepts, like all other concepts, embody shared rational standards. It was a deft and many-sided attack on the distinction between matters of fact and matters of value which had dominated English-speaking philosophy since the eighteenth century. Kovesi, as a newcomer to the English language and to the established traditions of philosophy in that language, was able to survey those traditions with a fresh and quizzical eye. His central thesis was that ‘Moral notions do not evaluate the world of description but describe the world of evaluation’. In his critical notice of the book in Mind, Bernard Mayo described it as ‘a lightning campaign of a mere 40,000 words which, I think, decisively and permanently alters the balance of power’ in the debate about fact and value. Its philosophical framework, as Mayo says, is ‘a general theory of concept-formation, meaning, and rules of usage’ which is used ‘to solve or dissolve an impressive list of standard problems in moral philosophy’.[7] Its argumentative strategy is to show that both ‘descriptive’ concepts (‘table’, ‘horse’, ‘yellow’ etc) and ‘evaluative’ concepts (‘murder’, ‘lying’ etc) can only function as concepts if they serve our rational purposes and needs.

Without our moral concepts and the standards they embody there could be no moral argument or disagreement. If we want to know what is moral then we must investigate the relations between our various moral concepts. The concepts and the distinctions between them constitute our moral knowledge. If we make the effort we will find in them a schematic rightness that we commonly overlook. And about this we have no choice, because we can only think by means of concepts. (Similarly, if we want to know about sport, or transport, or cookery, we need to investigate and master the relevant concepts. Only so can we work out whether, say, professional tennis is sport or business.)

In another way, however, it is the conceptual structure which can distort everything, and it may do so in ways which lie far deeper than ordinary mistakes of reasoning. Ideologies are ways of thinking in which a twist in the conceptual structure so governs our mental responses that we become unwitting victims of a systematic distortion. This is particularly likely to occur when one system of ideas is replaced by another. This is memorably illustrated by the Peanutscartoon referred to elsewhere in this book, in which Lucy, having at first mistaken a potato chip on the ground for a butterfly from Brazil then asks indignantly how a potato chip could have flown all the way from Brazil. Jean Francois Revel made the same point when he remarked that ‘our tendency to maintain habits of thought after we have abandoned the premises on which they were based, guides much of our thought today’.[8]

Ideologies not only mask hidden interests from those with whom we argue; they hide from ourselves knowledge of what it is we are really doing. They do this by eliminating from consideration those with whom we should be arguing. It is this that makes ideologies dangerous and permits us quite literally to eliminate our opponents. It is in this way that belief systems can be used as instruments of oppression. A society which institutionalised belief in peripatetic potato chips, and which treated those who called them ‘butterflies’ as mad or bad, would be an ideological society.

How are ‘ideologically distorted’ and ‘undistorted’ conceptual structures to be distinguished? More generally, if moral notions are collective achievements in which the interests of all parties are respected, and through which social life is made possible, how can whole social worlds be governed and dominated by radically unjust and intellectually absurd schemes of belief?

Kovesi wanted to draw a distinction between ‘closed’ and ‘open’ conceptual systems. As he outlines the distinction, an ‘open’ system is open to reasoning and evidence, and open to modification, even to refutation, in the light of that reasoning or evidence. Awkward facts, inconvenient arguments and evidence have to be listened to, and answered. A ‘closed’ system, by contrast, does not answer inconvenient reasoning and evidence; it explains them, usually as attacks on itself. To offer a reply would be pointless, or worse, since attack calls for counter-attack, not for reasoned reply. The ‘closed system’ purports to explain why the outsiders are attacking it, and why it would be out of place to listen to them seriously or to reason with them. So no fact, no event, no evidence, no argument can do any damage to a ‘closed system’; on the contrary, they all confirm and elaborate the truth of it.

Kovesi had a keen ear for illustrations of the ‘closed system’ cast of mind. He thought he could detect it in the dictum of Lukacs that the truth of Marxism would be unaffected even if every one of Marx’s assertions were shown to be false. He remarked on the combination of what he described as ‘the greatest possible “humility” with the greatest possible megalomania’ displayed in Teilhard de Chardin’s assessment of his own work:

In me, by the chance of temperament, education and environment, the proportion of the one and of the other are favourable, and the fusion has spontaneously come about–too feebly as yet for an explosive propagation–but still in sufficient strength to show that the reaction is possible and that, some day or other, the two will join up. A fresh proof that the truth has only to appear once, and nothing can ever again prevent it from invading everything and setting it aflame.[9]

That a system of concepts is closed is made apparent by situating it in a larger conceptual framework. But this will not fully explain why it is so difficult to break out of a closed system. The answer to that lies in the way in which the kind of closed system that interested Kovesi provided a ‘place’ for the believers or adherents of the scheme and a very different sort of place for those outside it. And since the schemes that he has in mind usually embody philosophies of history, this ‘place’ is (he believed) to be thought of as a role in a kind of drama.

As a moralist Kovesi expects that the scheme of concepts which constitute our moral life will assign me a place in my social order (parent, son, colleague, teacher, citizen etc.). ‘Places’ of this kind are not intrinsically objectionable. We could have no social life without them, or something like them. Dramatic placement is quite different; it provides its proponents with a privileged place which owes nothing to reason or morality. It is characteristic of ideological thought that in it the drama comes first, and the background concepts–upon which reason depends–are distorted to fit the requirements of the plot.

A further important consideration here is that Kovesi always kept distinct the issues that he regarded as ideological from those he saw as simply social or rational in the normal senses of those words. Some of the arguments for and against socialism (to do with economic efficiency, the power of the state and the bureaucracy, the value of personal liberties etc.) are in his view quite unrelated to the arguments for and against Marxism, so that a recognition of Marxism as ideology in no way constitutes an argument against socialism in any of its aspects.

Some will be inclined to dismiss these essays as ‘conservative’, just as Kovesi was himself often so dismissed. His opposition to communism, of which he had first-hand experience, and from which he had with difficulty escaped, was often brushed aside as ‘mere prejudice’. This kind of dismissal nicely illustrates all that he was concerned to argue against, and it can be used to show in simple form his moral theory working in harness with his critique of ideology. ‘Conservative’ used in this way as a term of dismissal is itself ideologically loaded, for it permits, indeed requires, the rejection of arguments on wholly extrinsic and irrelevant grounds. To ‘conserve’ is to do something which is morally neutral, but it is here being treated as a complete moral concept. That it is not a complete moral concept is easily shown by the fact that even those who use it in that dismissive way will themselves sometimes want to conserve things–historically-significant buildings, for instance. The real issue is whether, if Kovesi was in the business of conserving things, those are things that ought to be conserved.[10]

Kovesi’s thought was more a matter of questions than of answers. It is hard to recall any philosophical theories, other than his theory of concepts, which he can be said to have believed in. His lack of philosophical theories went deep. He once said that he thought that of all the great philosophical systems Spinoza’s was perhaps the most consistent. Had he not said so no-one would ever have guessed this to be his opinion. He was, it can be said, very little interested in the truth, in the sense of having a problem so well defined that we can start to talk about having the truth of the matter. He found from experience that it is far more important to get to grips with the kind of error that prevents us from even starting to think relevantly about what might be true. He thought most political discussion to be a form of moral exhibitionism. He never moralised. When a real moral issue arose–an issue about what to do here and now–he dealt with it mostly in silence, looking for the unexpected angle which might be the crucial one.

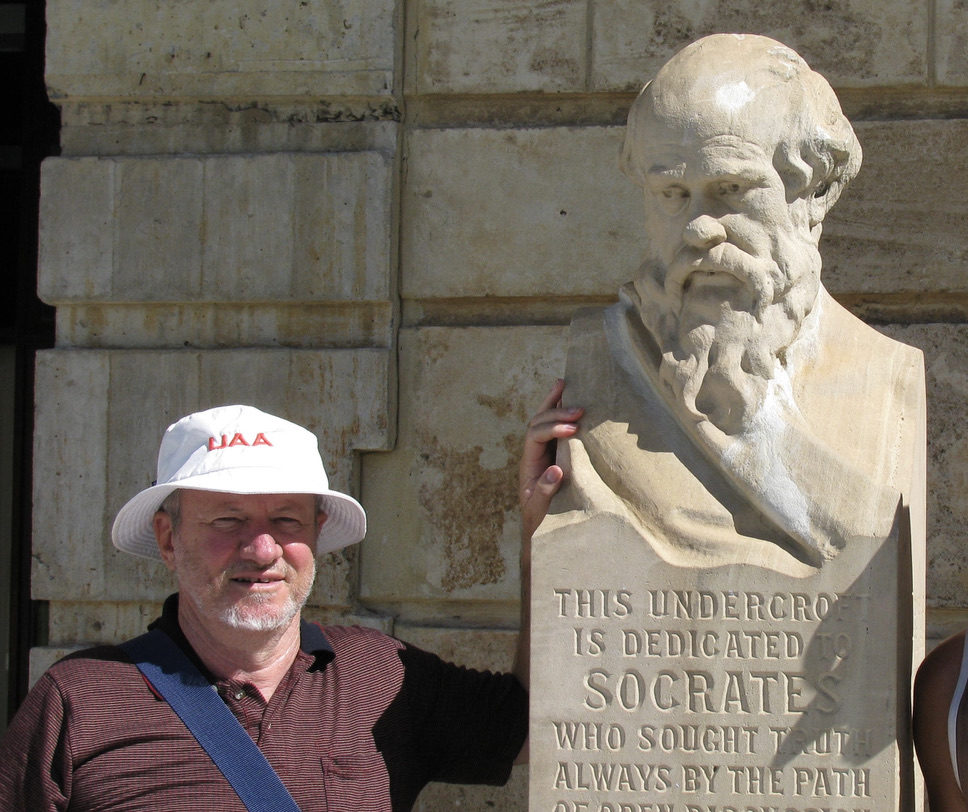

This lack of positive assertion came from the fact that he did not have answers to the many questions he thought we should be interested in. In place of answers there could only be puzzlement.[11] He had a remarkable capacity for puzzlement, for not even knowing what the question was when others were half-way towards working out their answers. If comparison was his characteristic strategy, puzzlement was his characteristic mode. On the surface this was playful, underneath it was not. The madness he sought most to combat was a madness which supplied answers without questions, and in this respect, as well as in his gleeful skill at drawing out unwelcome and unexpected conclusions to the arguments and assumptions of others, it is not unduly far-fetched to compare him to Socrates.

Most of Kovesi’s philosophy was an attempt to think about the conceptual tangles which bedevil our shared life. This made him very much a public person, though one who held few public positions. Throughout the turmoil of the late 1960s and 70s his door was shut only when he had a class or was talking with a student. He seemed to be perpetually in conversation, and like Socrates he practised his philosophy on his feet. This collection shows that he wrote more than we had realised. It represents him as a thinker, and indicates some of his qualities as a person.

[1] Their experiences with the Australian immigration authorities were amusingly described in an article Julius wrote for the Australian Observer (20th August 1960) entitled ‘Why Migrants Say No’. ↩︎

[2] It was the subject of an editorial in Philosophy, April 1976. See also Jill Paton Walsh’s novel, Lapsing (London: Black Swan Press, 1995), 217.↩︎

[3] See the Introduction to the theology section by Selwyn Grave, below page 90.

[4] Founded in wartime Oxford as an open forum for religious argument. C.S. Lewis was its first president. See Humphrey Carpenter, The Inklings (London: George Allen & Unwin, paperback edition, 1981), 214-16.

[5] See The Economist, July 15th, 1989.

[6] This deeply-rooted habit of mind also lay behind his (some would say deplorable) tendency to make puns. They were often rather bad puns, which depended upon a mispronunciation of English, and he was always pained when others did not immediately see the point. One of his children once explained to her sister: ‘Don’t you see, it’s not funny; that’s what makes it funny’.

[7] Mind, No.310, April, 1969. The effect, Mayo observes, is both ‘strongly original’ and ‘somewhat intoxicating’. ‘Time and again a startling paradox brings us to a halt, and we want a recapitulation of the steps in the argument that got us there. Nearly always we are driven back to realise that a favourite preconception has been subtly charmed away.’

[8] ‘Tom Wolfe’, Quadrant, Oct 1985.

[9] Teilhard de Chardin, Le Christique, as quoted in Robert Speight, Teilhard de Chardin (London: Collins, 1967), 330.

[10] On this see the end of ‘Nature and Convention’, below pages 139-151.

[11] The puzzlement rubbed off on his students, as it was intended to. One of them described the experience of trying to follow his lectures as like running past a garden and trying to see what flowers were in it through the cracks in the picket fence.