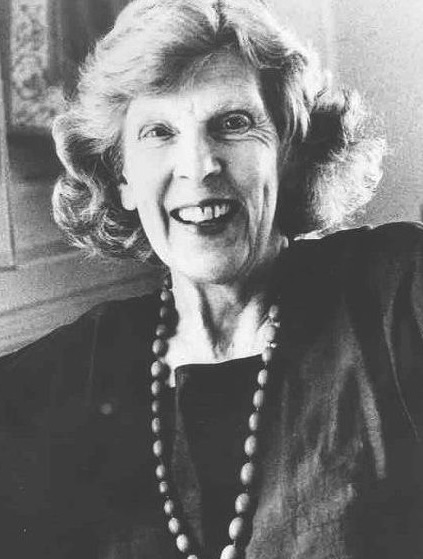

Philippa Foot

It was with real pleasure that I heard that Julius Kovesi’s Moral Notions was to be reissued, and I felt honoured to be asked to write a preface for the new edition. I had known Julius when he was at Oxford when he and I were allies – members of a small band of guerrillas fighting the prevailing orthodoxy of anti-naturalist emotivist and prescriptivisist in ethics, and challenging the Human doctrine of the gap between ‘is’ and ‘ought’. At that time we were rank outsiders and even in 1967 when Moral Notions was first published it must have been hard to get recognition for such an inconoclastic approach.

This time round I hope it will be different; though there will still be barriers to be overcome given the individuality of structure and even of terminology of Julius’s own theory of morals, which is radically different from anything else on the scene, either then or now. What is the difference? First and foremost it is that where most contemporary moral philosophers have as their starting point an account of what an individual speaker is doing (as e.g. expressing an attitude or issuing a prescription) when he or she praises or condemns an action Julius starts much further back with an account of the formation of a particular kind of concept. He sees moral thinking as above all formation of concepts such as murder or stealing and distinguishes such concepts form those which bring together such familiar objects as tables or houses: the distinction depending on the different place that operation with one kind of concept or the other has in our lives. We have the concept table on account of such activities as sitting down to eat, and its guiding principles (in Julius’s terminology its form) depends also on myriad other things that we do, such as furnishing houses and fashioning an marketing objects. Similarly, moral concepts are rooted in activities – but this time activities such as fault-finding and making decisions about behaviour – on account of which we fashion for ourselves classifications suited to these parts of human life.

It would not be suitable even to try to summarize here the sometimes puzzling details of the structure that Julius builds on this base. Instead I would like to in point out an affiliation that seems to me to be very important indeed. For while Moral Notions is like no other book of moral philosophy, it seems to me to have much connexion with Wittgenstein’s philosophy of language. Kovesi barely mentions Wittgenstein, but I would hazard a guess that he had deeply pondered Philosophical Investigations before he came to write the present book. Be this as it may, I think that Moral Notions will especially attract anyone interested in the philosophy of language considered from this point of view.

It is sad that we have a second chance to appreciate this remarkable book only after Kovesi’s death, and I myself much regret that I cannot discuss it with him. But we now have some further essays on moral philosophy reprinted in the collection Values and Evaluation edited by Alan Tapper, and I hope that these volumes will be read together and read with the pleasure and profit that this reading has given me.

August 2002